I read a lot of different financial blogs from a bunch of different sources. Last week, this article from “boomer&echo” caught my eye.

In it, they propose a “two fund” solution for how to invest in retirement:

- 90% of your funds in an all-in-one all-equity ETF (like XEQT, HEQT, TEQT, ZEQT1)

- 10%2 of your funds in a HISA ETF34 (like CASH.TO, CSAV or PSA)

They suggest funding your day to day spending needs from the HISA ETFs. Replenishing the HISA ETF comes courtesy dividends from the all-in-one equity ETF, and selling units “during up markets…or on a regular annual schedule”.

There are some things to like about this method, and some things not to like. I’ll break them down for you.

Like: It’s really simple

Two funds, and two percentages to remember. That’s simplicity. In a perfect world, my holdings would look similar, but would instead look something like

- 75% in XGRO (an 80/20 ETF)

- 20% in XEQT

- 5% in ZMMK

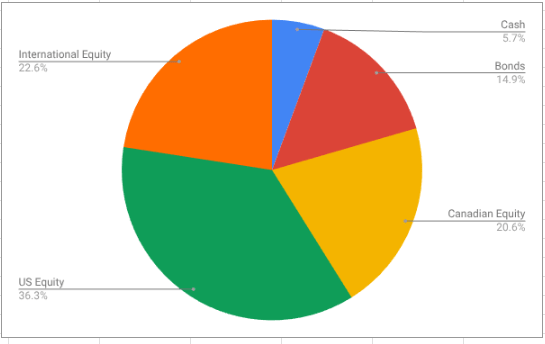

This breakdown would give me the 80% equity, 15% bonds, 5% cash that I strive for in my asset allocation targets.

Like: It’s broadly diversified (mostly)

Holding an all-in-one equity fund seems like you’re putting all your eggs in one basket, but as I discussed over here concerning XEQT, it’s actually a great way to make sure you have your investment spread out across many companies in many geographies. My one mild objection to this approach is that there are no bonds5 in the boomer&echo portfolio, but it’s a minor point.

Like: It recommends keeping cash in the retirement holdings

Having cash on hand is a good way to smooth out the gyrations of the market. It’s a fundamental part of my own withdrawal strategy.

Dislike: The approach is likely to get emotional

The approach to refilling the cash portion of the boomer&echo portfolio is left a bit vague in the linked article. “During up markets” is almost guaranteed to encourage daily agonizing over whether it’s really the “right” time to sell. “On a regular annual schedule” is better advice, but that’s a big trade to execute on a single day, and the temptation to delay this trade would be rather large, I expect.

Dislike: It may not be practical

In theory, it’s really nice to have a super-simple portfolio. In practice, it’s much harder to pull off when you have substantial non-registered investments. Making trades in your non-registered accounts to simplify your holdings may attract unwanted capital gains, which of course may attract unwanted taxes. Add to this my dubious practice of holding substantial USD assets, and you quickly go from an ideal to what a real retiree’s portfolio actually looks like. In any case, it’s always good to try to simplify wherever you can, like I did.

My approach: similar, but different

My approach to portfolio maintenance in retirement is similar to the boomer&echo approach, with a few key differences:

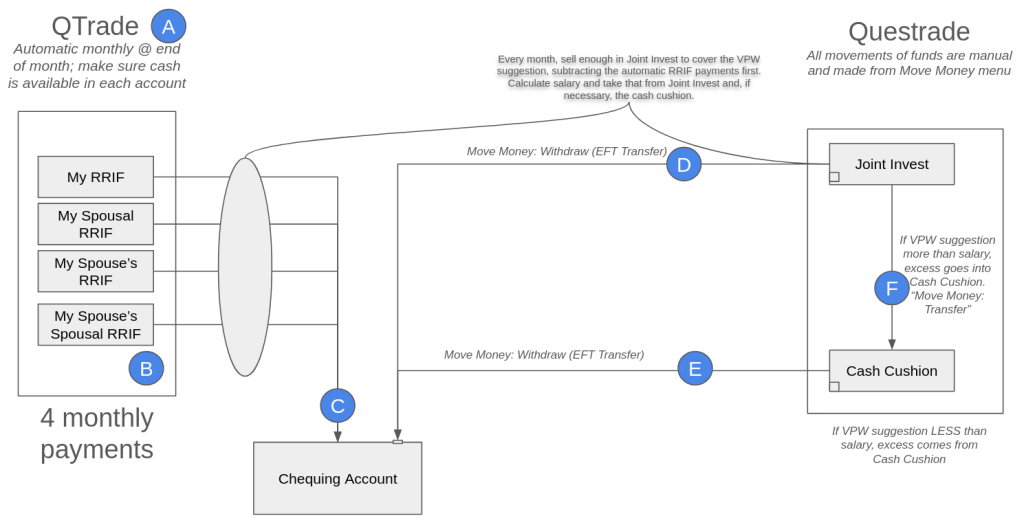

- Withdrawals are done monthly, without fail, and selling parts of my equity portfolio happen every month. No emotion, and I sell in up or down markets, on the same day every month.

- The 80/15/5 mix between equity, bonds, and cash is maintained at all times, plus or minus a percentage point. My multi-asset tracker spreadsheet helps with that. Extra trades might be needed in a given month to keep the mix correct.

- The cash portion of my portfolio is divided between a 6 month non-registered cash cushion that is part of the VPW methodology, and everything else. “Everything else” is largely in registered accounts so as to not generate unnecessary (and taxable) interest income.

What do you think about the boomer&echo two-fund approach? Anyone out there using it? Let me know at comments@moneyengineer.ca.

- The article in question mentions VEQT, but its MER is 0.24%, and the others are 0.20% or less. I hold XEQT myself. ↩︎

- Elsewhere in the article they characterize the HISA bucket as “12 months of withdrawals”, which is not at all the same as “10%”. ↩︎

- These kinds of ETFs invest in a variety of HISAs, like the ones I talk about here. ↩︎

- I use ZMMK in this role which is a bit riskier but with a bit higher return. Writing this article makes me wonder if I should head back to HISA ETFs instead. ↩︎

- Some research indicates that holding no bonds is in fact the best strategy. ↩︎