Using the Multi-Asset tracker, I can break out my retirement savings in any number of ways. Here we take a look at the breakdown of my retirement portfolio between RRIFs, non-registered Investment accounts, and TFSAs.

Using the Multi-Asset tracker, I can break out my retirement savings in any number of ways. Here we take a look at the breakdown of my retirement portfolio between RRIFs, non-registered Investment accounts, and TFSAs.

This is a (hopefully monthly) look at what’s in my retirement portfolio. The original post is here. Last month’s is here.

The retirement portfolio is spread across a bunch of accounts1:

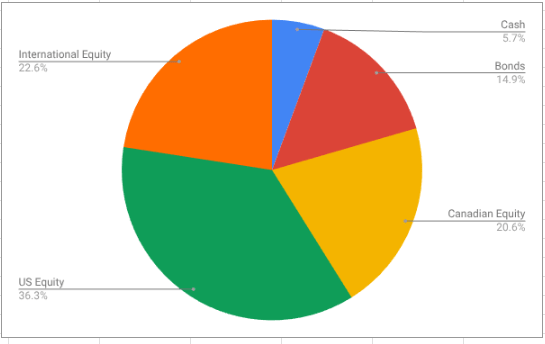

The target for the overall portfolio is unchanged:

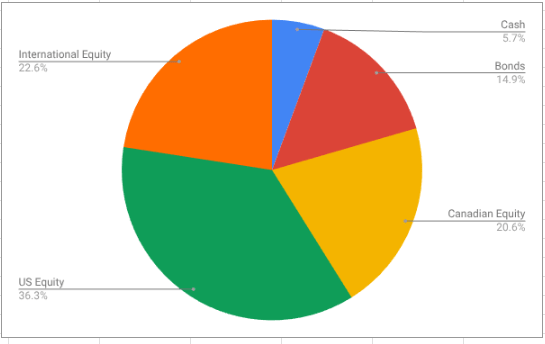

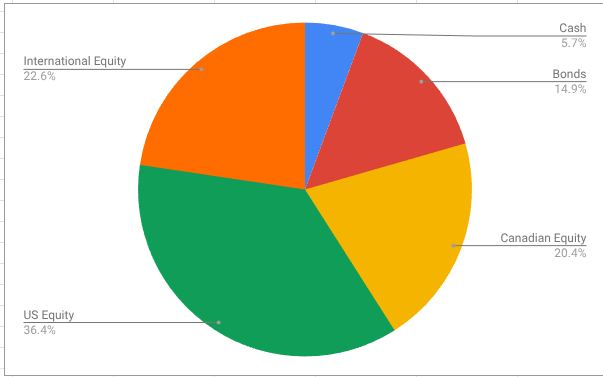

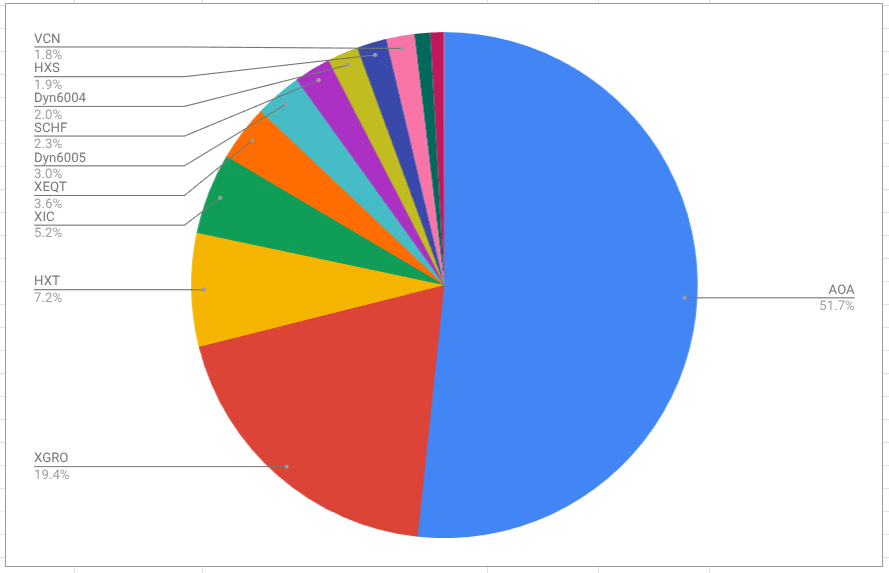

As of this morning, this is what the overall portfolio looks like:

The portfolio, as always, is dominated by AOA and XGRO which are 80/20 asset allocation funds in USD and CAD, respectively. The rest are primarily either cash-like holdings in two ETFs: ZMMK2 in CAD and ICSH3 in USD) or residual ETFs held in non-registered accounts for which I don’t want to create unnecessary capital gains just for the sake of holding AOA or XGRO.

The biggest month over month change is due to switching brokers. My old broker (QTrade) allowed the purchase of HISAs, but my new broker (Questrade) doesn’t seem to offer them4. So I replaced DYN6004 with ZMMK and DYN6005 with ICSH. I made these changes in my QTrade account to avoid any problems with doing an “in-kind” transfer to Questrade.

I’m still in need of USD to pay off some vacation bills, so there is a small hit to SCHF to help out.

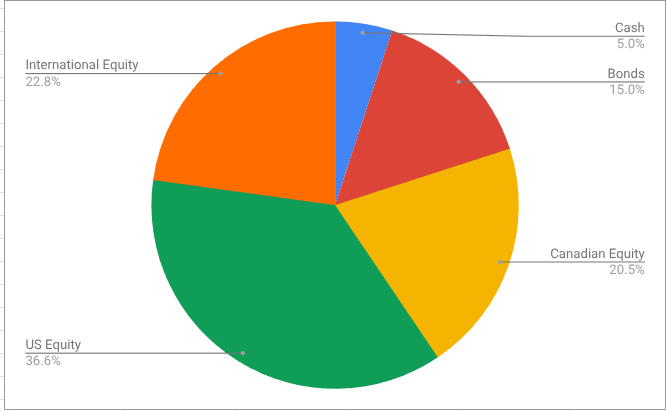

The asset-class split looks like this

The international equity percentage is below my target of 24%, and so I’ll have to fix that5. VEU looks like it provides exposure to both developed and emerging markets at a rock-bottom price6. XEF would be a perfect fit in the Canadian market, although I should probably also consider XEC to get some emerging markets exposure.The cash position is artificially high because I already did the necessary transactions to get paid out of my RRIF and non-registered accounts (if I did this exercise at the beginning of the month, rather than mid-month, that would disappear). That extra cash will flow to my bank account in the coming days.

A quarterly activity that I’ll be performing this month7 is to shift some of my USD RRIF holdings into my CAD RRIF. I do this to make sure I’m not overexposed to changes in the CAD/USD exchange rate. My current provider reportedly allows me to make RRIF payments natively in USD, so that may be another option to consider. I’ll make an attempt at some point!

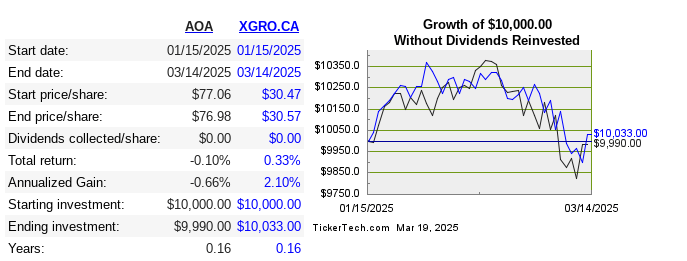

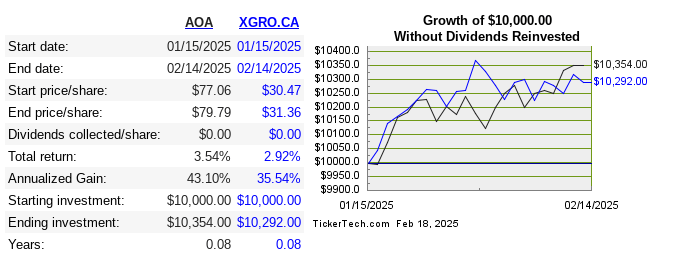

One final note: my retirement savings declined 3%8 over the month due to the wild (mostly downward) swings in the stock market, but this leaves me roughly even since my retirement started at the beginning of the year. Here’s the monthly returns for the 2 ETFs that make up the lion’s share of my portfolio9.

There are significant birthdays every DIY investor should be aware of. Did you know about all of them?

The list below is a gross simplification — like all things in the Canadian Tax code, the exceptions and caveats fill many pages, but this is roughly correct. I’ve included links so you can read the relevant sections yourself and see if you agree with my simplifications!

Per the feds, a birth certificate for your child is all you need to apply for a Social Insurance Number. And although their working days are far into the future, their RESP eligibility starts right away — but you can’t open an RESP for a child unless that child has a SIN. The lifetime limit for donations to an RESP is currently set at $50k/child. The sooner those contributions start, the sooner you can collect free money (the CESG, $500/year, $7200 per child lifetime), and the longer your contributions can benefit from the power of compounding.

This is significant one for a number of reasons!

Once you turn 181, you can open a TFSA and begin contributing. Even if you don’t start contributing, your TFSA limit starts to accumulate the year you turn 18. In 2025, that annual limit is $7000 per year, and it grows at the rate of inflation2. It’s cumulative, so it’s not a “use it now or lose it forever” kind of proposition. At the start of every calendar year, there are a flurry of announcements indicating the new annual limit.

You can contribute to your TFSA forever, even in retirement. I am!

If you’re over 18 and earn more than $3500 a year, you’ll have to pay CPP contributions. While current you may balk at this sort of reduction in your take-home pay, future you will appreciate the inflation-index adjusted salary you can collect later in life.

You can open a First Home Savings Account on your 18th birthday…or maybe your 19th birthday3. And the year you open it, you add $8000 in eligible contribution room…which continues every year, to a maximum of $40000.

The so-called “age of majority4” in Ontario allows you to roll in free money in the forms of GST credits, Trillium benefits5 (in Ontario) and carbon tax credits6 . The cost of admission is filing a tax return. No excuses — plenty of online providers offer free returns for “simple” returns and my friends at Wealthsimple offer “pay what you want” tax filing.

This is also a time you are eligible to open an RRSP7, which may make sense if you’re already maxing out your TFSA contributions.

An RESP can only be open for 35 years.

This is the first year you can choose to collect CPP; generally speaking, most experts recommend that you delay collecting CPP for as long as possible, for two reasons:

My tools page includes the very helpful CPP calculator, which can help you make a decision concerning your CPP start date.

This is the first year you can choose to collect OAS. Experts are a little more split on whether or not to delay this one — the benefits to delaying to age 70 are not as strong as for CPP8. My plan is to delay, as it’s another inflation-adjusted benefit.

If you’re collecting any sort of pension (RRIF payments, CPP, employer pension) this is the first age at which you can split that income with your spouse. This can reduce your tax bill.

You have to start taking CPP and OAS by this time.

You can no longer contribute to an RRSP and you have to open a RRIF. Lots of the literature out there seems to imply that this is the ONLY time you can open a RRIF, but rest assured, there’s no minimum age for opening a RRIF — I’ve been collecting from mine since the start of the year 🙂

This is the last year you can start collecting from an ALDA (advanced life deferred annuity) you have set up. The ALDA is a vehicle I just learned about, and need to do a bit more research. It may be a way to fund income in your later years when the complexity of managing withdrawals in a DIY fashion may be too cognitively overwhelming.

What birthdays are you thinking about? Let me know at comments@moneyengineer.ca.

This is a (hopefully monthly) look at what’s in my retirement portfolio. The original post is here.

The retirement portfolio is spread across a bunch of accounts:

The target for the overall portfolio is unchanged:

As of this morning, this is what the overall portfolio looks like:

The portfolio, as always, is dominated by AOA and XGRO which are 80/20 asset allocation funds in USD and CAD, respectively. The rest are primarily either cash holdings in HISAs (DYN6004/5 in CAD and USD) or residual ETFs held in non-registered accounts for which I don’t want to create unnecessary capital gains just for the sake of holding AOA or XGRO.

The biggest month over month change is due to a small re-balancing exercise. I replaced some of my XGRO (which is an 80/20 equity/Bond asset allocation fund) with XEQT (a 100% equity asset allocation fund). I do re-balancing any time my asset allocation drifts more than 1% off my target allocations3. The trigger for me was an overweighting in bonds, which had drifted to represent 16% of my portfolio instead of the desired 15%. Upon reflection, the reason was obvious: both AOA and XGRO are 20% bonds, and if I want only 15% bonds, I will periodically need to fund an all-equity alternative. The net effect will be that you will see more XEQT show up in the portfolio over time.

The observant reader will also notice a bit of a shift between DYN6004 and DYN6005. The reason? I raided some USD from DYN6005 to pay my US credit card bill and replaced it with CAD in DYN6004 using the spot FX rate at the time. Seemed the easiest way to get some USD4 without having to resort to my friends at Knightsbridge.

SCHF percentages drifted down a bit since that’s the ETF I’m selling in my non-registered portfolio to augment my monthly RRIF payments. That will continue for the next few months at least since the USD payouts are needed to fund a few holidays5 I’m taking that are billed in USD.

Otherwise, nothing interesting to see in the month to month changes.

The geographic split looks like this

The international equity percentage is below my target of 24%, and so I’ll have to fix that. SCHF seems a good choice in USD6 since it’s free to trade with QTrade. XEF would be a perfect fit in the Canadian market.

A quarterly activity that I’ll be performing this month is to shift some of my USD RRIF holdings into my CAD RRIF. This wasn’t something I had planned to do but since my provider has backtracked on allowing me to get paid out of my USD RRIF in USD, I needed a way to keep the USD exposure at a constant-ish level in the overall portfolio. I’ll talk about the USD in my portfolio in a future dedicated post.

One final note: my retirement savings continue to grow even though I’m now actively removing assets out of it. On paper, this makes perfect sense since an 80/15/5 portfolio ought to grow at a rate greater than my rate of removal. In practice, of course, it’s rather stock market dependent. Here’s the monthly returns for the 2 ETFs that make up the lion’s share of my portfolio7.

Summary: The mechanical details of getting paid in retirement require careful review of how your provider allows cash movements between accounts, a handle on how much money is coming in via a RRIF, and, for bonus points, an annual decumulation plan to minimize household taxes.

I covered how I get paid in retirement previously, but this was nothing more than a restatement of how VPW (Variable Percentage Withdrawal) works. My reality is not quite as simple as the Idealized Monthly Routine I laid out in that post.

The actual work required looks more like this:

The first 3 steps are the ones I covered in the last post, and there’s nothing new to talk about there. In brief, you calculate your retirement savings, enter that number into the VPW spreadsheet, and out pops the monthly VPW suggestion (“v”), which is then added to the current value of your cash cushion (“c”) to calculate your salary (“s”).

It’s probably worth noting what specific accounts I hold at my provider to make things a bit clearer1

So ideally, my RRIF payments would flow into the cash cushion account, and I would pay myself out of the cash cushion account to my everyday joint chequing account. That is unfortunately NOT how it works.

Let’s pick up the process starting at step 4.

When I opened my RRIF accounts (and yes, there’s more than one2), one of the questions asked was “what bank account should the payments go to?” Asking for RRIF payments to go to a non-registered account was not presented as an option, and it’s not possible. So already the simple RRIF to cash cushion transaction outlined in the ideal scenario wasn’t possible.

The other questions asked by my provider was: how much do you want to be paid? (RRIF minimum, some percentage/amount higher than that, gross/net?)

(If you’re new to the RRIF world, or if you think that RRIFs are just for 71-year-olds, you may want to check out my previous post on debunking this and other myths.)

The amount each of my RRIFs3 pays me monthly is a well-known fact since I opted to collect RRIF minimum from each RRIF — and RRIF minimum is based on my RRIF value and age as of January 1, 2025. It will stay constant throughout 2025. So while simple, the amounts involved aren’t enough to pay my suggested salary. I’m free to ignore the suggested salary and simply (try to) live off my RRIF minimums, but that would be counter to my “you can’t take it with you” ethos. And so, I have to augment my RRIF minimum salary with money from elsewhere.

If your RRIF minimum payments are higher than the salary, then I suppose it makes sense to re-invest those payments somewhere. Or give the money away. Up to you 🙂

The title is clear enough — sell something in the non-registered portfolio and use it to make up the salary shortfall. But whose holdings4? Which ones?

To help me decide, at the beginning of the year, I played around with tax scenarios using the calculators referenced in Tools I Use to concoct a high level plan on how to best minimize my household’s collective tax bill. (This was a tip my financial advisor gave me; her advice was to try to pay no more than an average tax rate of 15%5).

I assumed my income sources were

Since the first three items above were already known, there was no decision to make; the tax owing on those was already clear8. The capital gains were the only variable — how much should I take versus my spouse? There was a bit of estimation involved in the actual amounts here (the actual gains would depend on the actual sale price), but it gave me a high level plan for 20259. Any additional income needed would be paid by capital gains realized from MY holdings since my income was forecast to be lower than that of my spouse10.

With the pre-work done, it boils down to making the required sell trade, waiting two days for the cash to settle, and then clicking the right buttons to get the cash out of my investment account and into my chequing account. Should be simple, but if you’ve never done it before, you need to make sure it’s all working as you expect.

Yes, you have to make sure that there’s cash available in your RRIF accounts (and remember, I have 4) BEFORE the monthly payment goes out. My provider would only be too happy to do this on my behalf, charging me their “telephone trading rates” for the trade — something like $30 plus $0.06 a share for XGRO. Compared with “free” if I do the work myself, that’s a pretty decent hourly rate…Do not forget that it takes two days for a trade to settle into cash. Since my provider does not pay interest on cash holdings, I’m highly motivated to keep any cash balance to a strict minimum. I hate not earning money on my money.

In my previous post I talked about moving “v” to the cash cushion and then simply taking 1/6th of it as salary. And that is exactly what I do. But practically, it’s impossible to do this maneuver in exactly the way I describe with my current provider (QTrade). Here are the specific reasons I can’t do what VPW asks me to do:

I have worked around the limitations imposed by my provider by either

I have set up smart-ish spreadsheets to break down all the various movements of money which I will share at some point once I figure out how to make them a bit more generic. I’ve also documented a step-by-step guide for my spouse which she uses as we sit together walking through the monthly tasks12 so that I have confidence she could execute on them if I became incapacitated. There is no substitute for handing over the controls to see where the gaps in knowledge — and documentation — are.

Having witnessed what happens to savvy adults as they get older, I know deep down that this DIY strategy isn’t sustainable forever. There are too many moving parts, and too many opportunities to make mistakes.

At present, I don’t have a future plan mapped out. I have updated my “death binder“, but beyond this, nothing more. I will dedicate more research (and future posts) on that topic.