Using the Multi-Asset tracker, I can break out my retirement savings in any number of ways. Here we take a look at the breakdown of my retirement portfolio between RRIFs, non-registered Investment accounts, and TFSAs.

Using the Multi-Asset tracker, I can break out my retirement savings in any number of ways. Here we take a look at the breakdown of my retirement portfolio between RRIFs, non-registered Investment accounts, and TFSAs.

Summary: If you’re changing online providers with an active RRIF, the old provider is (apparently) obligated to pay out the ENTIRE RRIF amount for the current year before releasing your funds.

As you may have read previously, I’m (still) in the middle of changing online brokers from QTrade to Questrade1. Things are moving along…glacially2. I’m at step 6 of the guide.

If you’re not that familiar with RRIFs, you may want to give Demystifying RRIFs a read.

At QTrade, I had 3 separate RRIF accounts:

QTrade makes you have different accounts for CAD and USD, whereas Questrade does not (hooray)3.

The individual and spousal RRIFs are set up to pay out RRIF minimum on a monthly basis, on the last day of the month. I expect this is a little unusual, since a lot of people seem to take their payments annually. In a weird QTrade wrinkle, one can only make payments from a CAD RRIF account, even though the USD RRIF account is used to calculate RRIF minimums4.

The RRIF transfer-out requests were initiated the instant the RRIF account was approved by Questrade, in the opening days of March (March 2 or March 3), a day or two after my February RRIF payment was processed by QTrade. Plenty of time, I figured.

About 2 weeks ago now, I got a cryptic email indicating that my RRIF transfer out request had been rejected by QTrade due to having “insufficient funds for RRIF payout”. Looking at my QTrade account, it looked to me like the US RRIF was moving (QTrade had already kindly charged me the $150 transfer-out fee), but the CAD RRIFs showed no signs of a transfer being initiated.

Thinking a little about it, I realized that perhaps QTrade wouldn’t release the RRIF assets to Questrade unless they could be sure Questrade could make the monthly RRIF minimum payment, which strikes me as silly, but I expect there’s some regulation that makes this mandatory. And so I immediately sold a few shares of XGRO in each of the RRIF accounts to ensure enough cash existed to cover the RRIF minimum payments and re-initiated the transfer out request.

But again, rejection. What?

But that, apparently, was not fully correct.

Today, I was informed by QTrade that no, they are obligated to pay out the ENTIRE RRIF payment for the year before they hand off the account to Questrade. Given the state of the market, I’m not exactly jumping up and down at the thought of having to sell 9 months worth of RRIF payments all at once. (This was, after all, EXACTLY why I set up the RRIFs to pay out monthly.)

So, I’ve decided to leave the QTrade RRIFs alone for the time being. This is far from ideal (multiple providers breaks all my rules about retirement investments being simple), but I take solace in the fact that

All this to say that make sure you have sufficient funds to cover any anticipated RRIF payouts BEFORE initiating a transfer-out request!

This is a (hopefully monthly) look at what’s in my retirement portfolio. The original post is here. Last month’s is here.

The retirement portfolio is spread across a bunch of accounts1:

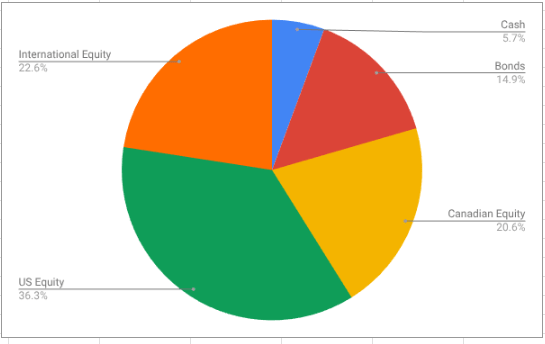

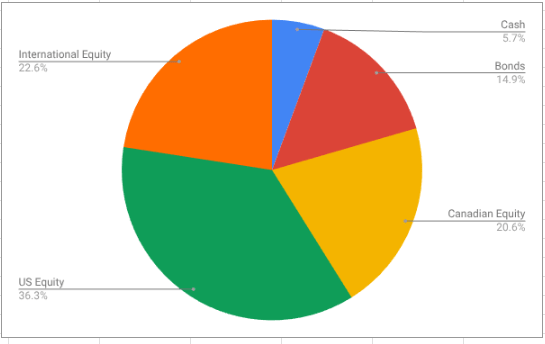

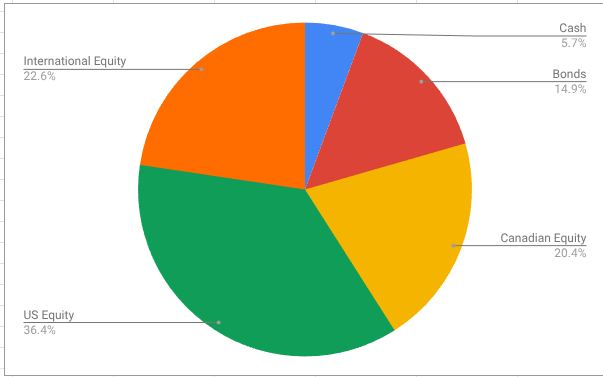

The target for the overall portfolio is unchanged:

As of this morning, this is what the overall portfolio looks like:

The portfolio, as always, is dominated by AOA and XGRO which are 80/20 asset allocation funds in USD and CAD, respectively. The rest are primarily either cash-like holdings in two ETFs: ZMMK2 in CAD and ICSH3 in USD) or residual ETFs held in non-registered accounts for which I don’t want to create unnecessary capital gains just for the sake of holding AOA or XGRO.

The biggest month over month change is due to switching brokers. My old broker (QTrade) allowed the purchase of HISAs, but my new broker (Questrade) doesn’t seem to offer them4. So I replaced DYN6004 with ZMMK and DYN6005 with ICSH. I made these changes in my QTrade account to avoid any problems with doing an “in-kind” transfer to Questrade.

I’m still in need of USD to pay off some vacation bills, so there is a small hit to SCHF to help out.

The asset-class split looks like this

The international equity percentage is below my target of 24%, and so I’ll have to fix that5. VEU looks like it provides exposure to both developed and emerging markets at a rock-bottom price6. XEF would be a perfect fit in the Canadian market, although I should probably also consider XEC to get some emerging markets exposure.The cash position is artificially high because I already did the necessary transactions to get paid out of my RRIF and non-registered accounts (if I did this exercise at the beginning of the month, rather than mid-month, that would disappear). That extra cash will flow to my bank account in the coming days.

A quarterly activity that I’ll be performing this month7 is to shift some of my USD RRIF holdings into my CAD RRIF. I do this to make sure I’m not overexposed to changes in the CAD/USD exchange rate. My current provider reportedly allows me to make RRIF payments natively in USD, so that may be another option to consider. I’ll make an attempt at some point!

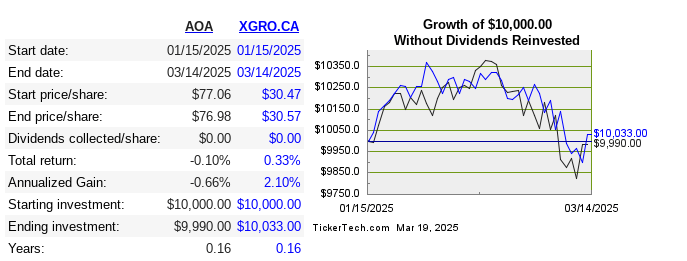

One final note: my retirement savings declined 3%8 over the month due to the wild (mostly downward) swings in the stock market, but this leaves me roughly even since my retirement started at the beginning of the year. Here’s the monthly returns for the 2 ETFs that make up the lion’s share of my portfolio9.

There are significant birthdays every DIY investor should be aware of. Did you know about all of them?

The list below is a gross simplification — like all things in the Canadian Tax code, the exceptions and caveats fill many pages, but this is roughly correct. I’ve included links so you can read the relevant sections yourself and see if you agree with my simplifications!

Per the feds, a birth certificate for your child is all you need to apply for a Social Insurance Number. And although their working days are far into the future, their RESP eligibility starts right away — but you can’t open an RESP for a child unless that child has a SIN. The lifetime limit for donations to an RESP is currently set at $50k/child. The sooner those contributions start, the sooner you can collect free money (the CESG, $500/year, $7200 per child lifetime), and the longer your contributions can benefit from the power of compounding.

This is significant one for a number of reasons!

Once you turn 181, you can open a TFSA and begin contributing. Even if you don’t start contributing, your TFSA limit starts to accumulate the year you turn 18. In 2025, that annual limit is $7000 per year, and it grows at the rate of inflation2. It’s cumulative, so it’s not a “use it now or lose it forever” kind of proposition. At the start of every calendar year, there are a flurry of announcements indicating the new annual limit.

You can contribute to your TFSA forever, even in retirement. I am!

If you’re over 18 and earn more than $3500 a year, you’ll have to pay CPP contributions. While current you may balk at this sort of reduction in your take-home pay, future you will appreciate the inflation-index adjusted salary you can collect later in life.

You can open a First Home Savings Account on your 18th birthday…or maybe your 19th birthday3. And the year you open it, you add $8000 in eligible contribution room…which continues every year, to a maximum of $40000.

The so-called “age of majority4” in Ontario allows you to roll in free money in the forms of GST credits, Trillium benefits5 (in Ontario) and carbon tax credits6 . The cost of admission is filing a tax return. No excuses — plenty of online providers offer free returns for “simple” returns and my friends at Wealthsimple offer “pay what you want” tax filing.

This is also a time you are eligible to open an RRSP7, which may make sense if you’re already maxing out your TFSA contributions.

An RESP can only be open for 35 years.

This is the first year you can choose to collect CPP; generally speaking, most experts recommend that you delay collecting CPP for as long as possible, for two reasons:

My tools page includes the very helpful CPP calculator, which can help you make a decision concerning your CPP start date.

This is the first year you can choose to collect OAS. Experts are a little more split on whether or not to delay this one — the benefits to delaying to age 70 are not as strong as for CPP8. My plan is to delay, as it’s another inflation-adjusted benefit.

If you’re collecting any sort of pension (RRIF payments, CPP, employer pension) this is the first age at which you can split that income with your spouse. This can reduce your tax bill.

You have to start taking CPP and OAS by this time.

You can no longer contribute to an RRSP and you have to open a RRIF. Lots of the literature out there seems to imply that this is the ONLY time you can open a RRIF, but rest assured, there’s no minimum age for opening a RRIF — I’ve been collecting from mine since the start of the year 🙂

This is the last year you can start collecting from an ALDA (advanced life deferred annuity) you have set up. The ALDA is a vehicle I just learned about, and need to do a bit more research. It may be a way to fund income in your later years when the complexity of managing withdrawals in a DIY fashion may be too cognitively overwhelming.

What birthdays are you thinking about? Let me know at comments@moneyengineer.ca.

I’m not sure when I first made a purchase of a USD-denominated ETF. Probably over 10 years ago. Clearly, I thought it was a good idea, because as of today I find that 57% of my retirement savings1 are denominated in US Dollars.

And unlike other people I’ve talked to, there’s no underlying rationale for that. I’ve never earned employment income in USD and I don’t own property in the US. So why?

I started investing in USD based ETFs simply because they were a much better deal than their Canadian equivalents. This is less true now than it used to be, but it’s still true. Take for example the comparison between comparable USD and CAD ETFs that track the same index:

| Index | What’s in it | USD ETF | MER | CAD ETF | MER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S&P 500 | Top 500 US stocks | IVV | 0.03% | VFV, XUS | 0.09% |

| Russell 2000 | 2000 mid-market US Stocks | VTWO | 0.07% | XSU2, RSSX3 | 0.36% for XSU, 0.25% for RSSX |

| FTSE Developed ex US | Global stocks outside of the USA | SCHF | 0.06% | VDU | 0.22% |

The Canadian market has become more competitive, and MERs have come down, but given the size of the US market, it’s still cheaper to invest there.

So although the MERs of US ETFs were stunningly attractive, I failed to consider the cost of currency conversion. For this I blame naivete as well as a lack of transparency on the part of my provider. It was not possible for me to easily figure out how much each CAD to USD transaction was costing me. A good estimate is about 1.5% the cost of the transaction, but some providers make this much cheaper5.

I also had USD investments in my TFSAs, which, from a tax perspective, isn’t the best idea.

Over time, I discovered the joys of Norbert’s Gambit to do currency transactions on the cheap and I became more savvy. And I eliminated all US holdings from my TFSA.

In preparing my portfolio for retirement (steps I took are outlined here), I did seriously consider converting everything to CAD in the interest of keeping things simple. I did not, and here’s why:

This isn’t working like I thought it would.

My provider decided to backtrack on allowing me to extract USD from my USD RRIF;7 we’re still going back and forth on that front, but my friends at QTrade are on my naughty list as a result. I’m not hopeful.

What it means practically is that although the value of my USD RRIF is used to calculate my RRIF minimums, I can only withdraw RRIF payments from the Canadian side. At present, the Canadian side of my RRIF will fund my RRIF minimum payments for a while, but at some point I’ll have to use Norbert’s Gambit to move funds from the USD RRIF to the CAD RRIF.

I don’t think that holding USD assets in retirement — especially in a RRIF — is a great idea for the DIYer. Unless platform providers give really clear processes8 for how to extract that money from a USD RRIF, expect trouble.

At some point, I will either switch providers to find one that supports my requirements9, or I will convert everything to CAD. Right now, I have a process that works, but older me I expect will find it too complicated.