We’ve talked about asset allocation / asset classes before in this space, most recently here. But while watching a recent post1 from one of my favourite experts, The Loonie Doctor2, it occurred to me that it might be helpful to start right from the beginning.

And to me, that beginning is understanding WHAT to invest in. Broadly speaking, you can choose between three categories: “Equity”, “Bonds” and “Cash”.

“Equity” refers to stocks of publicly traded3 companies. Owning stock means you own a piece of the company you invest in. This allows you to collect dividends if and when the company pays them out. If the company fails/goes bankrupt, the stock becomes worthless.

“Bonds” are essentially loans to companies or governments4. When you buy a bond, you’re buying into a stream of interest payments that stop when the bond is paid off. If a company who issued the bond fails/goes bankrupt, bond holders legally get first dibs on whatever assets remain in an effort to get their money back, but it’s possible that there isn’t anything left to fight over. Bonds can be fully paid off in various timeframes, from very short (30 days) to very long (20 years).

“Cash” is the money that’s left. Cash can be invested in things like high interest savings accounts, GICs/Term Deposits, Treasury bills (aka T-Bills), or stuffed under a mattress5. There is definitely a grey area between “Cash” and “Bonds” since both involve lending money to an entity. Shorter duration loans are more cash like. Lending to governments and large corporate entities (like banks, which is what you’re doing when you buy a GIC) is more cash-like. Money under a mattress is absolutely cash, albeit not really an investment at that point.

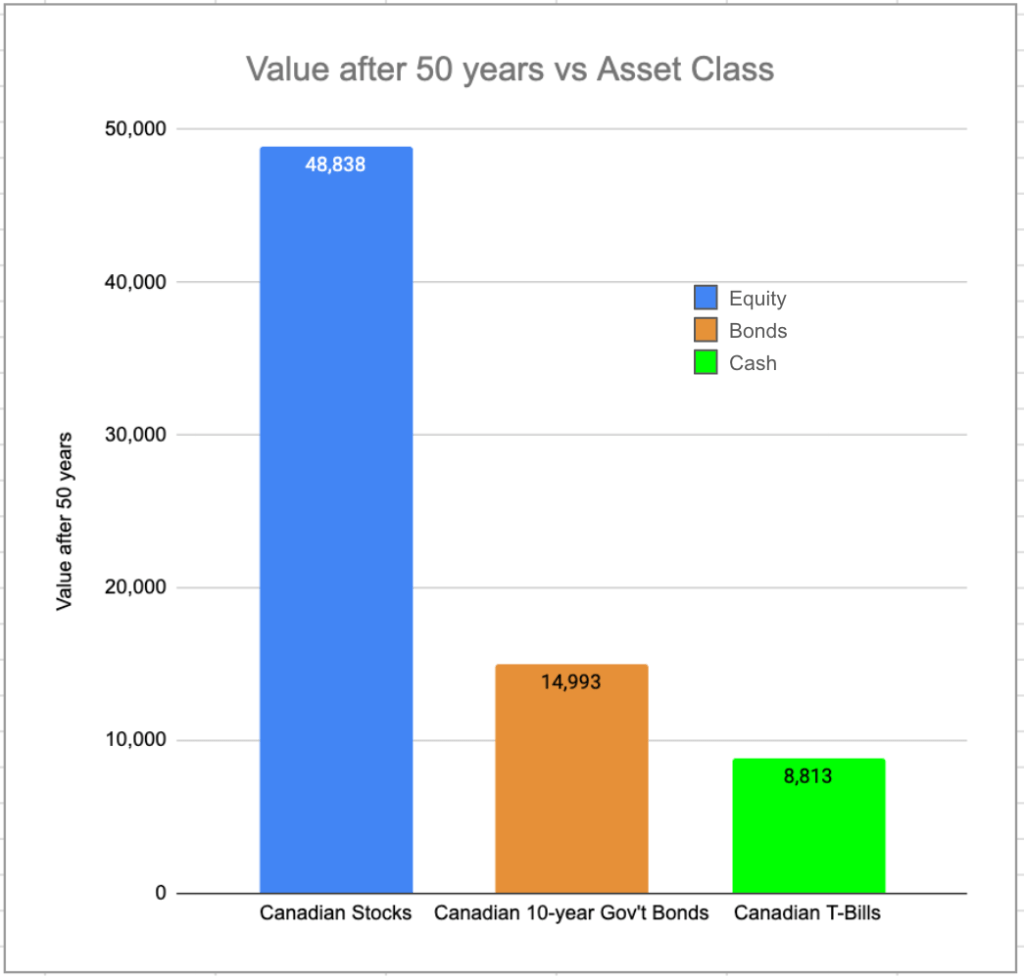

Using the data tabulated here, you can build a chart like the one below to see how much the $1000 investment you made in each of these categories would be worth 50 years later6.

Looking at this chart, it should be reasonably obvious that equities, represented here by Canadian Stocks, over time, generate the best bang for your invested buck. The “over time” phrase is very important, because otherwise, one could rightly ask, “why would anyone ever invest in anything other than stocks?”. The reason is volatility — in any given short time period, your returns could look very, very bad indeed. Just one example (of many) — the TSX has LOST money in 3 of the last 10 calendar years per https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%26P/TSX_Composite_Index.

Bonds, generally speaking7, have a much steadier and predictable return, often uncorrelated with stocks. When stocks go up, bonds often move in the opposite direction. And cash, well, its benchmark is the inflation rate. If cash is returning the inflation rate8, then at least you’re standing still.

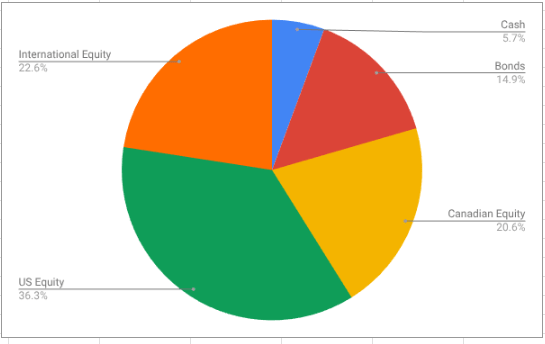

In my investment portfolio, my target allocations are 80% Equity, 15% Bonds, 5% Cash. Using products like all-in-one ETFs and my handy-dandy multi-asset tracker spreadsheet make this relatively easy to track. In my next post, I’ll show how to identify ETFs in each of the categories.

- Which provides further justification that using all-in-one ETFs is really the best approach. ↩︎

- Which, while positioning itself as being for doctors, has a ton of useful information for those of us who are not physicians as well. ↩︎

- And of course it is possible to buy stock in private companies (so-called private equity) but since I don’t know very much about that world, I figured I’d keep it simple and just talk about things that are available to the general public. ↩︎

- And the financial stability of those companies and governments can vary a lot. That’s where bond rating services can point you to higher quality entities (with a low risk of not paying) or lower quality entities (with a higher risk of not paying, but a better interest rate — the bottom of the barrel here are called “junk bonds”). ↩︎

- AKA “the chequing account of most major banks”, which don’t pay any interest ↩︎

- For “Canadian Stocks” this is the TSX Composite index (former name: TSE 300). “Canadian Bonds” is 10 year Government Bonds. ↩︎

- Let’s forget 2021-2 ever happened to the bond market. ↩︎

- And it doesn’t always do so! ↩︎