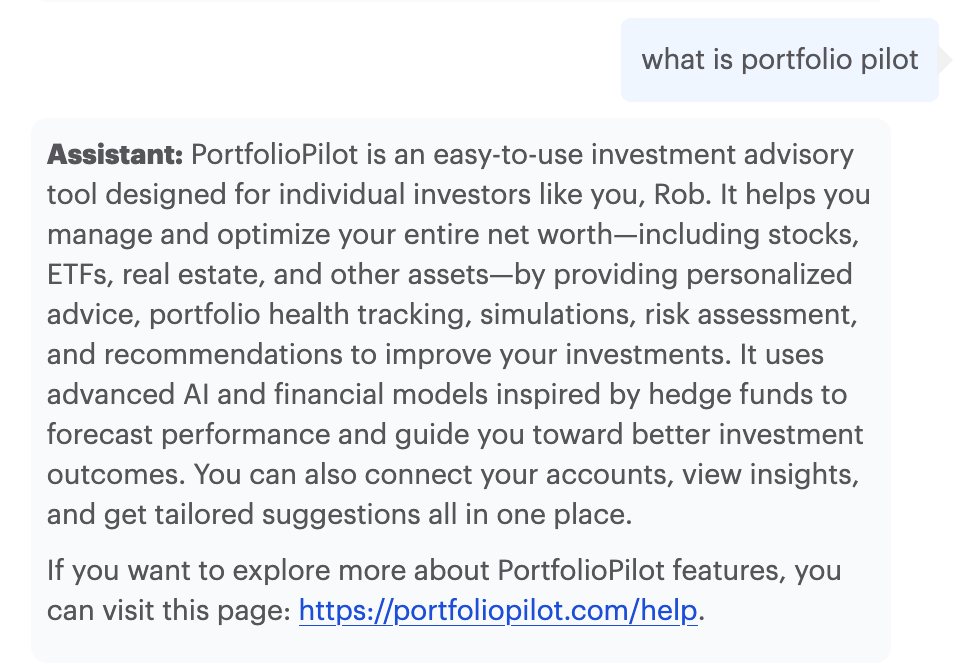

I discovered PortfolioPilot (https://portfoliopilot.com/), a product of Global Predictions, because it’s mentioned in passing on Passiv’s dashboard. (You can read a bit about Passiv over here — the premium version of Passiv used to be offered for free to all Questrade users, but it’s now part of their shiny new subscription service1.)

So what is PortfolioPilot? Let’s hand it over to their AI assistant to weigh in on that question 🙂

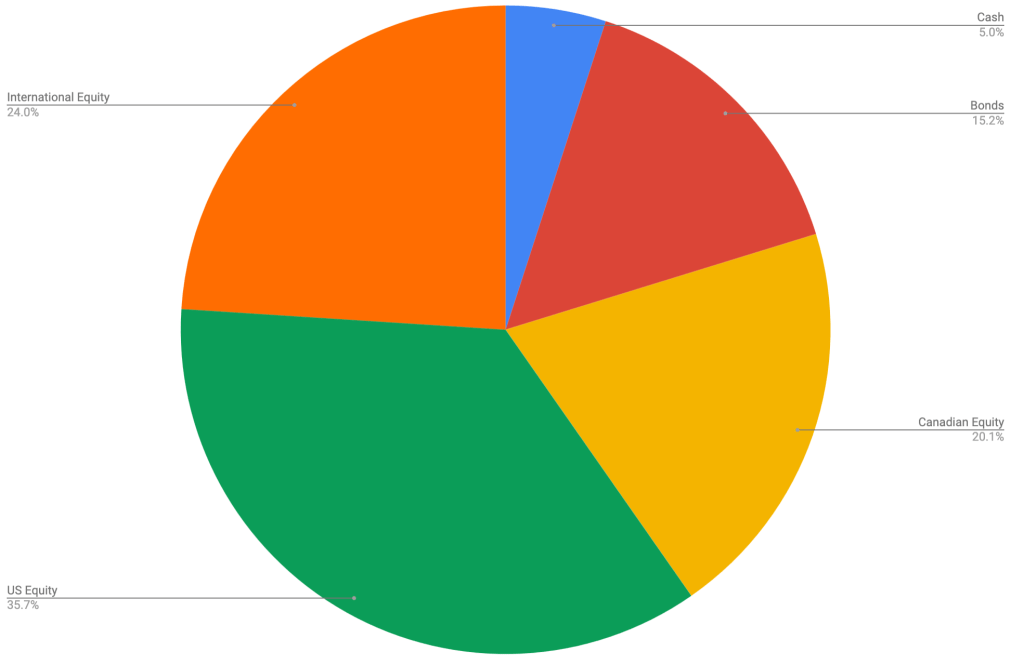

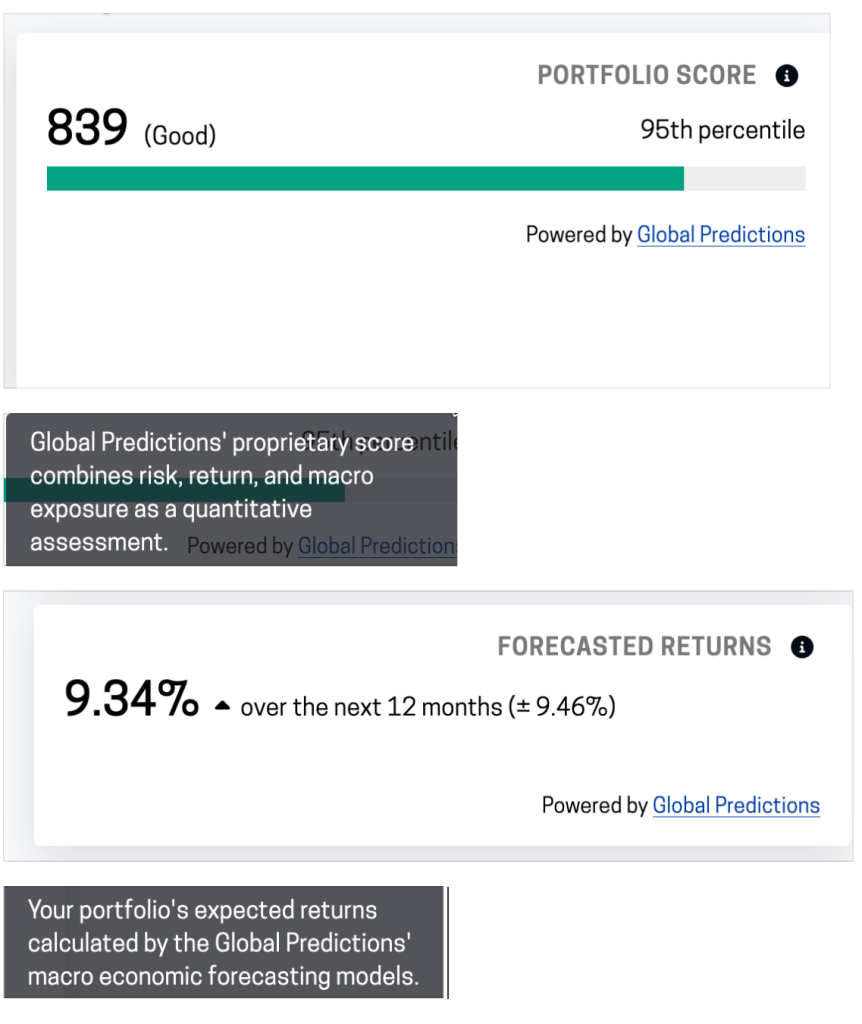

On Passiv, the data provided by PortfolioPilot is limited to a portfolio score (out of 1000) and a “Forecasted Return” metric. The Global Predictions/PortfolioPilot assessments for my portfolio as presented on the Passiv dashboard are depicted below.

When I headed over to the PortfolioPilot website, I decided to set up an account and take a closer look.

After an initial set of questions to help figure out my risk profile, I was able to enter my entire portfolio manually, since it’s down to just 12 holdings these days. Pro tip: this is a US tool, so if you enter Canadian stocks/ETF, you have to add “.TO” to the name of the holding in question, e.g. XGRO.TO not just “XGRO”.

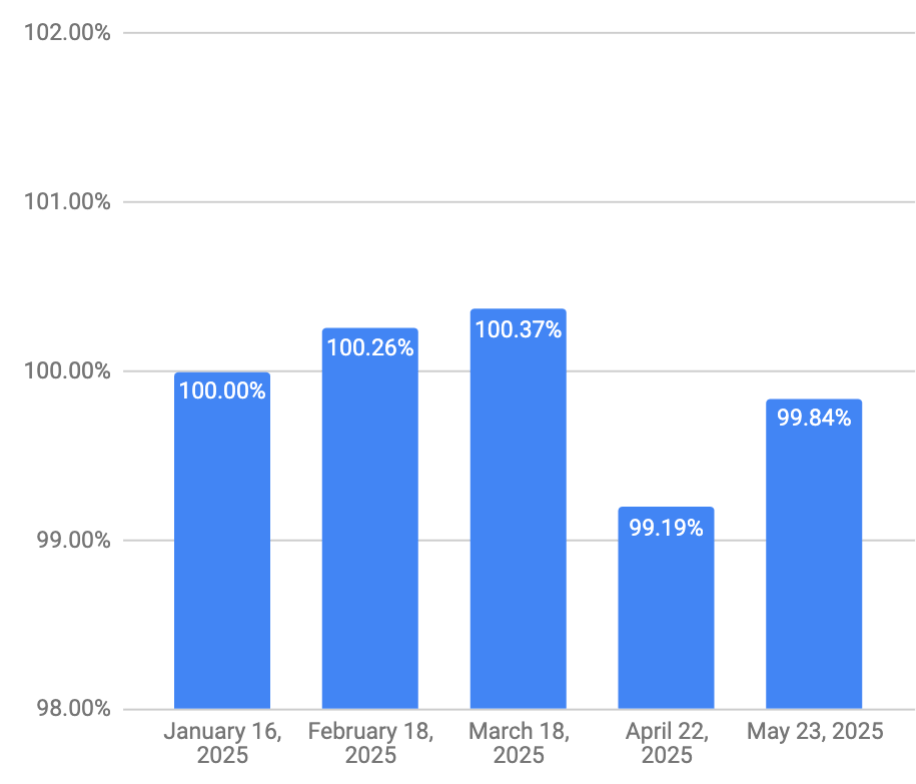

So once I did that, it spat out all kinds of pretty data. I do like the visualization per ETF held…this one is showing 3 month returns per ETF. Whether or not it’s including dividend payouts is not known.

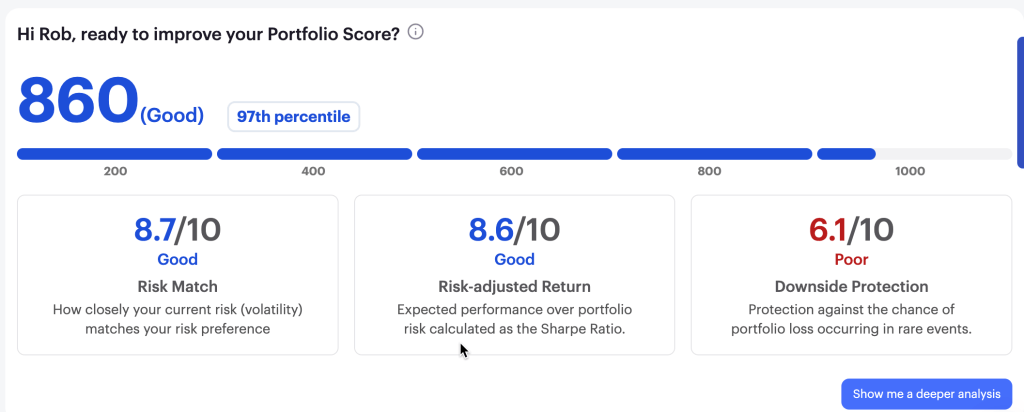

It also gave me a little more insight into my portfolio score4:

This view reminds me of how QTrade does their portfolio assessments, something I thought was a plus of that provider. The downside protection warning indicated that I have too much invested in too few holdings, but since I’m on the free version, no further insight was provided. Both AOA and XGRO are tilted towards large US stocks…I suppose my Magnificent Seven holdings are a non-trivial part of the overall portfolio as a result, but I wasn’t able to delve further into this warning. That’s what you get for paying nothing, I suppose.

So some nice stuff here, nice visualizations, customized news based on what’s in your portfolio, all good. But there are some problems I see with their data.

Example one:

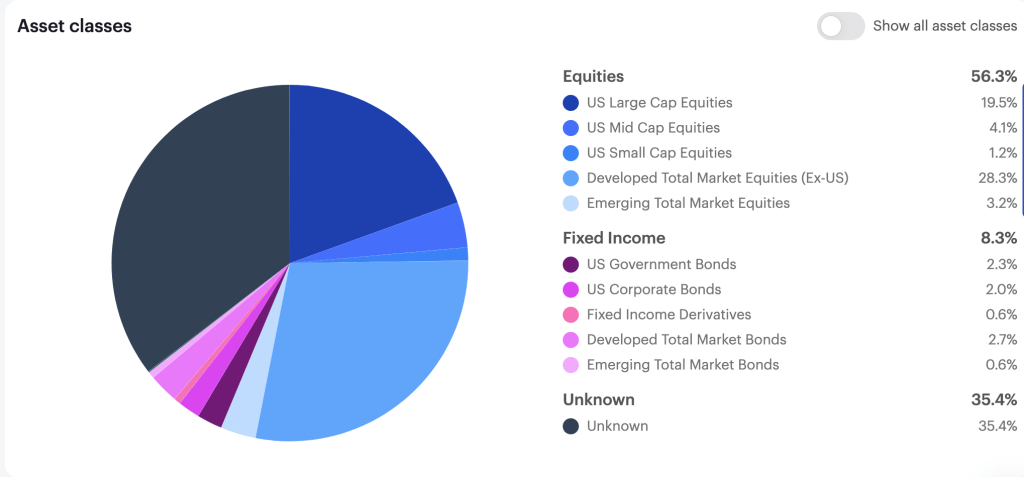

The asset breakdown is very detailed, which I like, but at 35% “unknown”, it’s kinda useless. No way I can see to figure out what ETFs are causing it trouble. Guess I’ll see what support has to say.

They have specific recommendations, which I also like, but again, I see issues:

So here, my issue is with action #2. It was recommending replacing XEQT (an ETF all-star) with VE.

Now, setting aside for a moment that VE and XEQT are pretty different in terms of what they hold, (to start, VE has no Canadian or Far East exposure), the REASON the suggestion was made was to save on management fees. PortfolioPilot claimed that VE attracted no fees, making me a sucker for paying 0.20% to hold XEQT. A quick look at the VE page dispelled that idea immediately — the MER is 0.22%. Following their advice would have led me to pay MORE in fees, not less. Shrug.

Anyway, I spent all of 30 minutes with this tool, and although it shows promise, some of the errors I spotted do not fill me with confidence in recommending it to others.

Anyone out there using it? Got other thoughts? Let me know at comments@moneyengineer.ca!

- But per some Reddit threads I have seen, users with more assets with Questrade may get it anyway. I await some sort of official communication before commenting further. As of right now, I still seem to have full access to the tool. ↩︎

- I dunno, 95th percentile seems “Excellent” to me.

↩︎ - Not really sure how to interpret that. Does that mean between 8% and 10% annual return, or does it mean -1% to 19% annual return? I would tend to believe the latter, since that’s more in line with an 80% equity portfolio, but no explanation is offered… ↩︎

- I suppose my score is a bit higher because it also includes my remaining QTrade holdings, which Passiv doesn’t support. Or maybe not. ↩︎