I had an email from a reader this week (via comments@moneyengineer.ca, I read all the email I get) who was curious about the yield of my retirement portfolio. It occurred to me I haven’t really talked much about this topic, so thanks for the inspiration 🙂

A very common approach for retirement investing is to build a portfolio based on high-quality dividend-paying companies. The best example I can think of is the long-standing “Yield Hog” portfolio written about by the Globe and Mail’s John Heinzl. He updated readers at the end of 2025.

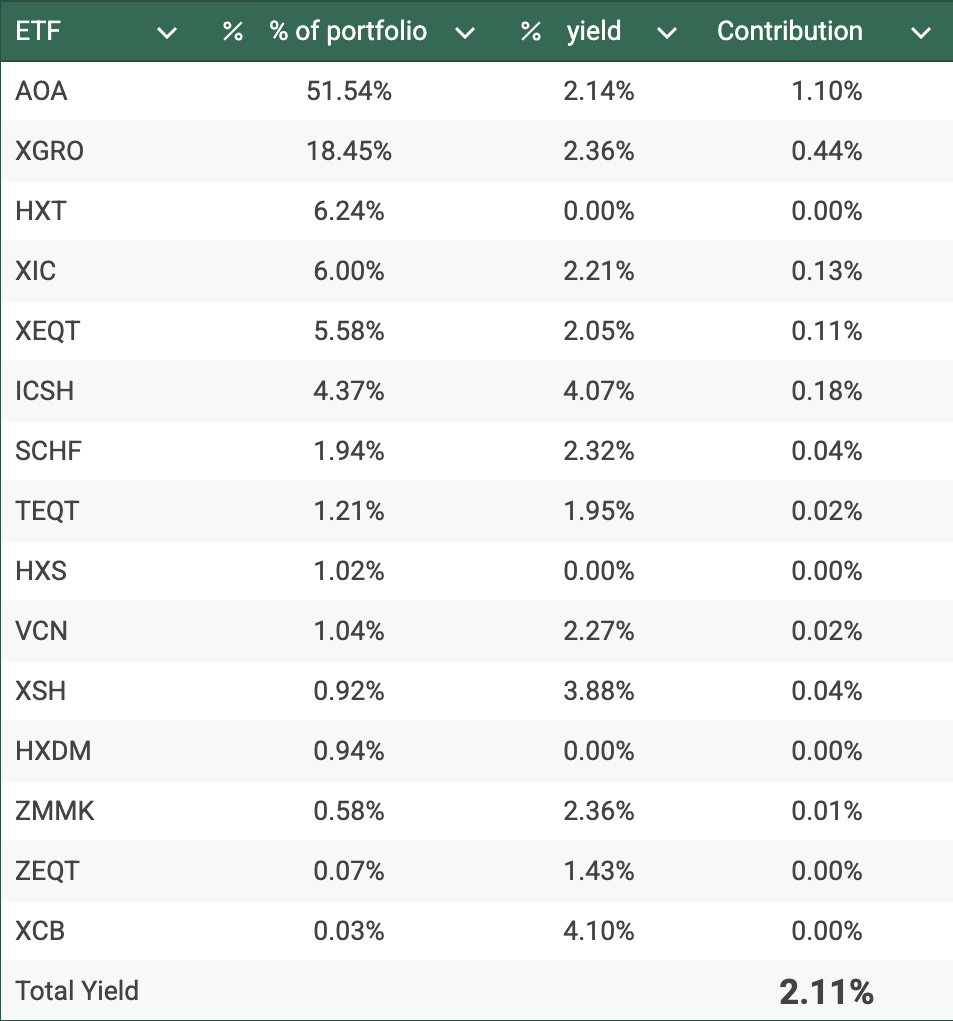

So, using the ETF fact sheets1 and my current holdings, I give you the overall yield2 of my retirement portfolio:

So the overall yield is just a little north of 2%. For a divided investor, this would seem alarmingly tiny.

If building an income stream from this portfolio was your objective, you’d either have to have a lot of capital, or very modest income needs, as this portfolio is only generating about $20k in dividends for every $1M invested.

For me, I’m perfectly happy to dip into capital (i.e. sell ETF units) to fund my retirement. The overall growth of the portfolio is my only consideration, and whether that is in the form of dividends (which, in my portfolio, are always reinvested3) or capital appreciation (i.e. the price of the ETF increases) is irrelevant to me.

Is it possible to build a dividend-focused portfolio just based on ETFs? Sure. But here I do offer a word of caution. The ETF providers out there have learned how to structure products with spectacular-looking yields that either use leverage (and are hence inherently more risky) or boost their yields by using RoC and giving you back some of your own money. So looking at yield numbers alone without understanding what’s inside the ETF is not a good idea. I took a look at one reasonable product (ZGRO.T) in a previous article.

The Globe has been my go-to trusted source for such things for a long time; they have annually updated ETF lists in various categories, including dividend ETFs. One that jumps out for me on this list due to its very low cost to own4 (which is something I’m a bit fanatical about, admittedly) is XDIV.

XDIV’s current yield is 3.93%, and holds large Canadian companies like TD, Royal Bank, Manulife, Sun Life, Suncor Energy, Power Corp…In total it holds only 21 companies, with never more than 10% invested in any one company5.

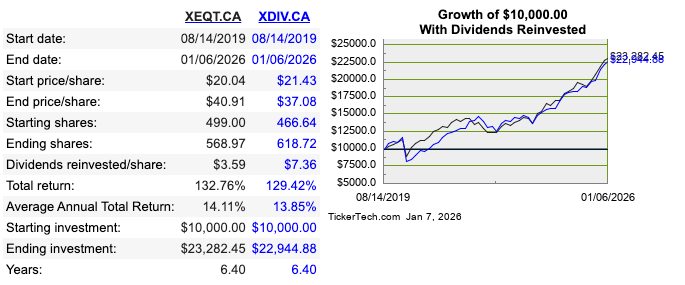

Just for fun, I did a head-to-head comparison of XDIV versus XEQT using this calculator that is featured in Tools I Use. I chose XEQT even though it’s a smaller portion of my portfolio than XGRO, but is a better stand-in since XGRO holds bonds.

So here it’s practically a tie. If you reinvested all the dividends for both ETFs, XEQT would have generated about $300 more on an initial investment of $10000 in August 2019.

But is that really a good comparison? XEQT and XDIV are pretty different:

- XEQT adds extra fees because it rebalances automatically between its different geographical holdings

- XEQT invests globally; XDIV is limited to Canada only.

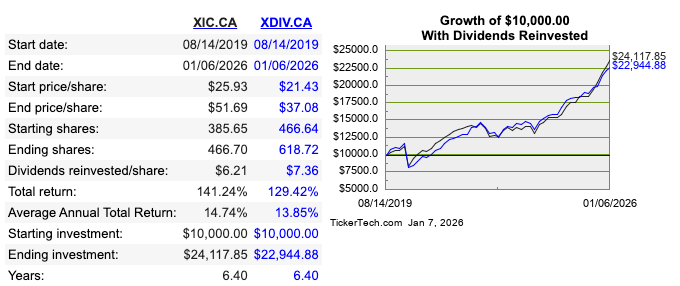

What if I instead chose to compare the Canadian portion of XEQT to XDIV? (I broke down what’s inside these all-in-ones in a previous article: Under the hood of XEQT et al). XEQT’s Canadian portion is XIC, an ETF that tracks the entire TSX (219 stocks), so let’s run the numbers again over the same time period:

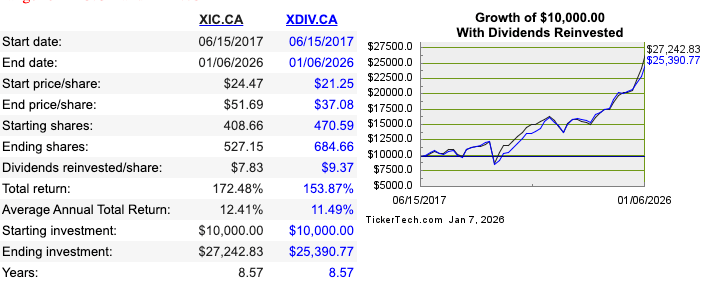

Here the gap is more noticeable: XIC outperforms by about $1200 in the same time period, assuming all dividends are reinvested. Now, of course, you can see that sometimes XDIV was ahead during this period. I cranked up the timeframe to as far back as I could to see what the results were:

Adding two more years of retrospective increased the gap by another $800, which is about a 1% per year return advantage to XIC.

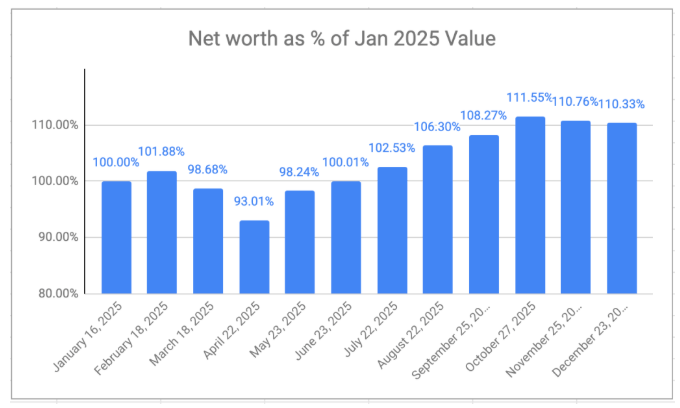

Now of course, you could find counter examples I suppose. But if capital preservation isn’t a concern6, then these results tell me that dividends needn’t be a concern in retirement. Even with my anemic yield stats, my net worth increased in 2025 even accounting for getting paid every month (chart from my latest What’s in My Retirement Portfolio):

Every month, I sell XGRO shares to fund my RRIF payments. Every month, I sell some non-registered assets to cover the rest of my salary. The TFSA gets a monthly contribution. Selling shares isn’t bad — as long as those that remain keep growing, I can keep spending7!

- TEQT isn’t publishing a yield, so I made an attempt to calculate it based on the Dec 31 distribution. This seems a bit lazy on TD’s part: I get that it’s a new ETF, and 12 months of data isn’t available yet, so you can’t show a trailing yield, but you CAN show the forward looking yield based on the most recent distribution. Banks. Sigh. ↩︎

- A weighted average. You may wonder about HXS/HXDM — these are “corporate class” ETFs that by design do not make distributions and instead use accounting tricks to bury that growth inside the ETF price. It’s something I use in my non-registered accounts. ↩︎

- Either automatically via DRIP or through my own purchases; it’s a bit of a mix at the moment. ↩︎

- A MER of 0.11%, a bargain for this sort of ETF. ↩︎

- Otherwise, its tracking index (MSCI Canada High Dividend Yield 10% Security Capped Index) has a TERRIBLE name. ↩︎

- For me, it isn’t. I’m not looking to leave a large estate. Die with zero! ↩︎

- And if they shrink, so does my spending. That’s the VPW way. ↩︎